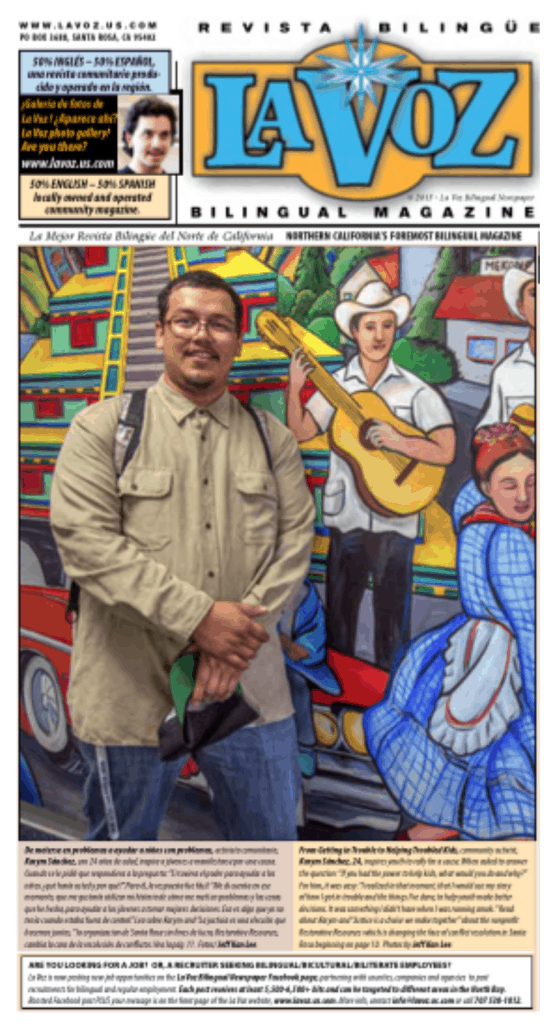

Karym Sánchez, 24, inspires youth to rally for a cause

Karym Sánchez, 24, inspires youth to rally for a cause

This profile of North Bay Organizing Project youth organizer Karym Sanchez is reprinted with permission from La Voz Bilingual Newspaper of Santa Rosa County, CA. (Photo by Jeff Kan Lee)

Karym Sanchez still remembers the title of the essay he submitted for the Juvenile Justice Commission annual teen essay contest.

“It was called ‘The Importance of Decision Making,’” he says.

At the time, he was 17 and had just come out of “a dark place.” A few months before, while his parents were going through a divorce, Karym was living, unsupervised and undocumented, out of his car in Riverside, while his mother was living in Santa Rosa and his father had been deported to Mexico.

“On the same day I was expelled from Ramona High School in Riverside for possession of large amounts of marijuana, later that same day I got arrested for stealing alcohol from a Walgreen’s, while driving there in a friend’s car that had been stolen,” he says. After his mom picked him up from jail and brought him to Sonoma County, Karym wound up in the Santa Rosa Community School, a continuation program that was effectively the end of the line.

Nowhere Else to Go

“No one got expelled from there,” he says. “There was nowhere else to go.” One day at school, his assignment was to write an essay to submit to the annual Juvenile Justice Commission contest. Staring at a blank sheet of paper, he had to answer the question: “If you had the power to help kids, what would you do and why?” For him, it was easy: “I realized in that moment, that I would use my story of how I got in trouble and the things I’ve done, to help youth make better decisions. It was something I didn’t have when I was running amok.”

The essay wound up winning first place.

At the time, the recognition was flattering, but after graduation he forgot all about it while working endless odd jobs.

Words Become Reality

Four years later, he was working mostly with his hands as a farmer and taking the occasional class at Santa Rosa Junior Class where he discovered MEChA and the North Bay Organizing Project. After landing a job with Restorative Resources, he came face to face with the same essay he’d written at 17. It turns out a Restorative Resources counselor was a Juvenile Justice Commission essay judge and still had a copy of his essay.

“Sitting there in front of me, the words were manifested into reality,” he says. Working for Restorative Resources, the non-profit pioneer in the rising field of restorative justice, he found his goal of “helping youth make better decisions” was no longer a dream. He was now in charge of the grassroots Accountability Circles Program, which worked directly with kids who had been arrested or expelled from school. It gave them a second chance to take responsibility and make amends for their wrongdoings. Funded by a $900,000 grant from the Department of Corrections, it was one of the most cutting-edge restorative justice programs in the country.

This same program would later prove instrumental in changing the way Santa Rosa city schools dealt with discipline, during a time when the district was facing a disproportionate number of Latino student suspension and expulsions.

Rising Latin Star

Now, at 24, Sanchez is one of the rising stars in the Sonoma County Latino community and a leader in the activist platform that is the North Bay Organizing Project. Still working part-time for Restorative Resources, running a circle-keeping program at the Sonoma County Juvenile Hall, he works full time as a community organizer and coordinator of the NBOP Latino Student Congress.

His role is to help youth learn how to organize and rally around a cause. It involves inspiring middle school and high school students to represent their Latino clubs and groups at a monthly student congress meeting at Sonoma State University. But it also includes taking students, many who have never taken part in a march, to events like the anti-fracking rally in Oakland in February. Or teaching students that environmental justice is not just a rallying cry for “white folks who shop at Whole Foods and drive a Prius. Because environmental justice affects poor and brown people the most.”

Finding Their Power

Working with North Bay Organizing Project since August, 2014, he’s learned how to show youth that power often lies in knowing how to make a concise list of demands. “They have to learn how to polarize somebody in a public office and ask, ‘Are you going to do this for our community or not?’ That’s how they’re really going to build power and affect change.”

His heroes include obvious icons like Cesar Chavez and Che Guevara, but other inspiration lies closer to the heart: “My great-grandmother, I’m standing on her shoulders. She was protesting issues and living conditions down in Mexicali many years ago, so I come from a long line of community organizing. It’s something I’m very proud of.”

To rally his people around a cause is in his blood and it’s become his life’s calling. “I always want to be fighting for justice where ever justice needs to be fought for. Eventually I want to be a player in statewide California issues. If I go to Sacramento, it’s not just because I believe in an issue. I go there because I brought thousands of people with me.”